This memoir finished 1st in the 2023 Hal Prize competition for nonfiction. I’ve thought it would have been published by now, but it has not and as it is my story to tell, I’ll publish it here, now.

There are two reasons to get a PET scan; one, if you have cancer and two, if they think you have cancer. Either way, it’s a serious business. I had never had one before and didn’t know what to expect. Two days into what eventually proved to be a five-day trip I found myself in a three-walled cubicle with an off-white curtain on a metal rod hung across the open end that reminded me of a shower curtain. My cubicle was the center of three which faced three more across a six-foot space that was closed to my left but had a door to my right through which I had come and through, presumably, which I would exit. Four hours earlier I had seen the pulmonologist, two hours earlier had completed my Pulmonary Function Tests, and one hour earlier had visited the lab for what seemed about twenty tubes of blood and a bottle of urine. I was surprised my skin was still relatively pink. I can understand why people come from all over the world to be seen at the Mayo Clinic. Even though I was in the medical profession myself, never would I have guessed that so much could be done in so little time.

Before the RN with the name badge that said Rachel closed the curtain, I saw the man in the cubicle directly opposite. For some reason his shower curtain was still pushed all the way to the side. Maybe he was claustrophobic. Then the door opened, and Rachel came in with another tech who wheeled him out. As he passed in front of me, he turned his head and we exchanged glances, small smiles, each not knowing if the other knew that they knew if they had or had not cancer. He looked to be about sixty, balding, completely grey, thin, didn’t obviously look emaciated, like he had cancer, like a cancer was eating him away; but then, neither did I.

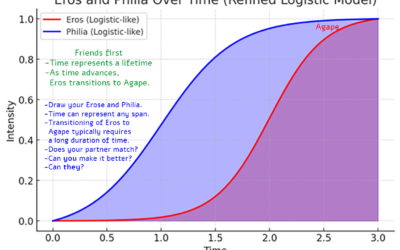

PET stands for Positron Emission Tomography and for it to work for cancer detection you have to be fasting for at least four hours so that your blood sugar is low because the first part of the test involves starting an IV and then transfusing a radioactive glucose. Since you want the tissues to take up glucose, it doesn’t do that as well if you are starting from a fed, high glucose state. The tissues that are metabolically more active, like cancer and inflammation will take up the radioactive glucose more than the “normal” tissues, and this is where the magic happens. The radioactive atom attached to the glucose molecule decays or breaks down and particles are released, one of the particles released is a positron. A positron is the opposite of an electron, which holds a negative charge, and they cannot coexist; when a positron is emitted, it immediately encounters a normal electron and the two annihilate each other, which you might say is like a nuclear explosion except that it is on a sub-atomic scale, the end result being the release of two photons, containing the energy of the electron and positron that are no more, which means light. The PET scanner detects the light from this sub-atomic nuclear reaction, and there is more light in malignant cells than normal cells and this shows up on the PET images; blue-green is not so bad, yellow-orange not so good, and red is very bad.

“Here comes that little poke I told you about.” I could tell she’d been doing it all day every day for a long time before I even felt the needle, how she went from the flat yellow tourniquet around my upper arm, to the alcohol swab brushed over my antecubital fossa, to the needle poised above the theoretical median cubital vein in my arm in about five seconds. I couldn’t see vein, so I knew should couldn’t as well. I said that I was fine, that I was used to it by now. She was so fast I didn’t have time to tell her to aim for the mole that I know is right above the vein because that’s what they used when I used to donate plasma twice a week in college at $20 per.

Rachel taped the IV up and plugged me into the radioactive glucose on the IV pole sticking up from the bottom corner of the gurney. It looked like water to me, in its clear plastic bag with blue lettering and a big red stop sign that I suppose meant to make sure you’re giving it to the right person.

“Looks pretty innocuous,” I said to Rachel.

She let her hand rest on the top of mine and gave me a little squeeze, like we were shaking hands backwards or something. “It’s a good test, Dr. M. I gather you know how it works?”

“I do indeed, just never had one before.”

“It will give useful information for your doctors, as you know.” She smiled and for some reason I felt better. “Now, remember, Dr. M, just lie back and relax, no reading, no cell phones, there’s no TV in here so obviously that’s not an issue. We have to wait an hour for the transfusion to work.”—she looked at a crucifix hanging on the wall to my right, it was opposite a clock symmetrically positioned on the wall to my left— “Just…be still,” she said, like she was Jesus on the storm-tossed sea of Galilee trying to bring me peace, and I was…still. Strange. I had a brief vision of her walking on water in a storm-tossed sea, the wind whipping her wet hair across her face, scrubs soaked through, name badge fluttering in the currents of air like a wounded bird.

“Thank you, Rachel,” I said.

My stillness and peace left shortly after Rachel. Do you know the last time, other than before sleep, that I was alone with my thoughts, trying to be still; no music, no book, no kindle, no paper, no computer/phone/tablet/movie screen/TV, no news, no talking, no nothing? Yeah. I don’t know either.

At first, I started with Hail Mary’s, which I do at night before sleeping after my usual partial rosary, from the crucifix to the little medal connecting the junction of the strand of beads, which has two big beads on either side of three small beads, which means The Apostles Creed/crucifix, an Our Father/big bead, three Hail Mary’s/little beads and a Glory Be/big bead; only then do I do more decades, if I need to. I rarely get past three, counting them off on one hand with folded fingers, five down, then straightening my fingers, not necessarily in order just to mix things up, five up. Then, with palm flat against the bedsheet, two Our Father’s, then repeat.

I got bored after a couple of decades and so I said some Act of Contrition’s in case something bad happened, like if I had a heart attack or something because I heard somewhere once that if you say an act of contrition before you die you can go to heaven even if you have a mortal sin on your soul. My act of contrition is not a standard one because it’s not like the one in the missalette. It’s one that I remembered when I was like ten-years-old, or less, but I’ve been saying it ever since, and the last time I said it in front of Father at confession, he didn’t say anything, so I inferred that it was still proper. Next up was Shakespeare. I can’t say I ever really understood it or enjoyed it immensely, but I memorized a ton of it and still, to this day remember it, so it took me another ten minutes to work through Mark Antoony’s monologue from Julius Caesar, you know the one, Friends, Romans, countrymen, lend me your ears…Then Hamlet’s To be or not to be, that is the question, and later in the play, or maybe before, Hamlet’s speaking to Rosencrantz, the paragon of animals and quintessence of dust…then I heard another man from behind the curtain opposite in the cubicle to the left. The tech, not Rachel, another one, was asking him what the PET scan was for, and he said that he had bladder cancer that had spread to his lymph nodes but that he had been enrolled in a clinical study and the doctors wanted to see if the tumor burden had shrunk, wanted to see if it was working. Bladder cancer is difficult if it escapes the bladder. It’s something that can’t be cut out then. It’s up to the medicines. His voice wavered and in it I could hear the fear I felt, and I didn’t even know if I had cancer yet. In the cubicle to my right, I heard Rachel with someone, but I couldn’t hear through the wall what she or the patient was saying. I remembered seeing one other person in the waiting room when I left and figured it must be him: another man, with a tracheostomy, Asian, younger than me, obviously throat cancer. When my name was called, we looked at each other and nodded, understanding our common connection from across the universe of humanity.

I looked at my watch, amazed that they let me keep it, given the mental stimulation of watching the second hand go around and around. The big hand and little hand said 9:30. A glooming peace the morning with it brings; The sun, for sorrow, will not show his head. The last line of Romeo and Juliet slipped through my mind, a streamer of thought that bubbled up, unbidden. The sun? Was the sun out now? Did the sun show its head today? Suddenly, it seemed important, a harbinger, but I was in the middle of a brick and stone edifice, deep in the basement in the places where they keep things like PET scanners and big magnets. I didn’t remember seeing the sun this morning, but it was early. Twenty minutes passed. Was that all? Still forty minutes to go? I started to feel claustrophobic, deep in the basement, in a small room, even if one end closed off only by a thin white curtain. I remembered my MRI scan, the knocking noise, the smell of laundered sheets and alcohol swabs and the small metal tube barely fitting around my shoulders, and I disappeared into it, nothing but a not so big metal tube about the size of a coffin. It was hard to breathe. Then I thought I should probably think of something else because maybe I was breaking one of the rules by watching the stupid TV in my head so I started singing to myself the Beatles song Yesterday, all my troubles seemed so far away…and that helped. I started to relax. To be still.

I heard the door open and someone saying “…over here on the right.” I saw a younger woman, pushing a small child in a wheelchair past the narrow gap between my curtains, then their curtains opened and closed. I couldn’t figure out why the space between my curtains didn’t line up with that of the cubicle across the hall because they were directly opposite, but they didn’t. I wasn’t sure if I should even be looking as if that might count as thought and effort that might mess up my glucose metabolism.

A young voice asked, “What’s a PET scan do?” I couldn’t tell if it was a boy or a girl.

“It’s a very special test that lets the doctors see inside your body. It’s like X-ray vision—”

“Like Superman?”

“Yes. Something like that, and like Superman, your doctors can use that information to help make you better.”

“Oh.”

I had a vision of a small boy in my head. I had no idea if it was him or not, but I could see a thin boy with large brown eyes in a face so pale, with skin so thin it was almost translucent, revealing delicate blue vessels underneath. He wore a stocking cap because his head was bald from chemotherapy and was always cold. I knew what was next. I heard the little boy start to sniffle, then cry as the IV entered his skin, and then a woman’s voice talking to him, a low soothing voice, saying words only he could hear.

“It’s okay, Darrell, we’re all done.” I heard the tourniquet snap free, a final shuddering sob, the woman’s there, there sweety; then, “I’ll stop back and check on you and your mommy in a little bit. Your job now is to just lay back and try to be quiet, like it’s nap time at school.” The curtain hung with metal loops on a metal rod opened and closed, footsteps from soft-soled shoes moved left to right, the door to the right closed with a final soft click; then a total silence, like waking up in the middle of the night alone in a strange place.

“Am I going to Heaven, Mommy?” His voice was clear and distinct, with no attempt to whisper, like they were the only ones in the room.

“Not yet, precious.” Her voice was more quiet, soft, and surprisingly strong. I could feel the tears forming in my eyes and that pressure in my chest reaching up into the base of my throat I feel when I feel like I have to cry but don’t want to because I didn’t want anyone to hear or see because it seems like something they shouldn’t, like it wasn’t proper. How she could be so calm when I could barely keep myself together?

“Will I see Papa when I do go there?

“Of course, you’ll see Papa when you go there, sweety, and you’ll see me—” Her voice broke, a fracture in the calm, but then she continued in an even softer, lower voice, almost a whisper but not quite and I couldn’t hear what she was saying, and then I heard it.

A woman humming. It had to be his mother. It sounded like it was coming from right across from me, but then I was less certain. Was it from the room to the right of the little boy that I thought was empty? No, it was a women’s voice. It had to be her.

The melody was a classical hymn that everyone knows, but I couldn’t say the name at the time, and I still can’t remember exactly what it was other than it was perfect. It was absolutely beautiful, and somehow, without even realizing it, I couldn’t say exactly when, the humming transitioned to words of comfort and solace, in a lullaby of love that I’m sure I’ve heard before but couldn’t name, a song of songs for her child so that he might cast off all the fear and trepidation and pain, for at least some small measure of time, that the entirety of his illness had entailed to that point.

At first, it didn’t feel right that I should be eavesdropping on such an intimate exchange of love, but then I realized that although she was singing to her son, although her entire focus was on him alone, the center of her world, her love within, for him, was universal, meant for all. She was the embodiment of love, and I remembered that verse from the bible, God is love, and whoever abides in love abides in God, and God abides in him, or in this case, her. And I knew she was singing to her child, and I knew she was singing to me, and she was singing to the man with bladder cancer to my left, and to the person in the cubicle next to me that I heard Rachel talking to through the wall because a love like that cannot be contained. It was/is transcendent of time and place.

Her compassion and love were palpable, a physical presence in that large room of six cubicles sharing a narrow common space. She sang for I don’t know how long, her voice raised, clear and penetrating like an aria you’d expect to hear on an ornate stage in a far away place, from a beautiful lady in an exotic costume singing the music of the genius of men, inspired by God to write down what was in their heads. It’s like time ceased to pass, call it eternity if just for a moment, and when my curtain opened for me to be taken to my scan, I was unaware that she had stopped. I turned my head to hide the tears in my eyes, and as the gurney was pushed out of the room, through the small space between curtains I saw a little boy with a purple Minnesota Vikings knit cap. I could see his mother’s hand holding his, but I didn’t see her. As I passed by the last cubicle next to the door, I saw that it was empty, the gurney freshly made, and although I didn’t see it, a crucifix on the wall, opposite the clock on the other. Be still, I told myself, but I couldn’t. I straightened my head, not caring about the tears running down my face or my own shuddering breaths as I was wheeled down the hall, for I had heard the sound an angel makes.

0 Comments