Who isn’t interested in love? Who doesn’t spend a lifetime failing or succeeding in one of life’s primary endeavors? Who doesn’t enjoy the physiological aspects of love, or approaching those aspects by the reading or watching of it at some point in their lives, perhaps, at times, going full immersion beyond what might be considered morally just or even physiologically healthy? Even St. Augustine could not say, “Not me,” which gives me the spiritual cover to add, “Not me either.”

In fact, I’ve been thinking of nothing less for the past two-plus years during the writing of a novel titled appropriately, if poorly, The Song of Songs. True to form, I wrote it as though an expert, as though I knew all about love, as though I had the pedigree to tackle such an epic design. My defense is that it’s fiction; still, in fiction lives truth and a potential for emotional growth.

I wish I had read C.S. Lewis’s The Four Loves first, not because I missed the mark entirely, but rather that perhaps I would have approached the mark differently. As I read it, I found myself wondering if there would be a way for one to assign an objective mathematical value to love based on standardized questions and use that to derive a function, something more complex than a quadratic equation, perhaps more akin to Schrodinger’s wave equation by which you could answer the question I am a good lover? Or How could I be a better lover? As I am not a mathematician I dare not start there. Instead, I must start with C.S. Lewis, henceforth known as CSL.

A main tenet of the Christian faith, as illustrated in John 4:8, is that God is love; however, this is not particularly helpful, as we don’t know what God is beyond being ineffable, which means we’ll never fully comprehend the whole of it. CSL was quite clear in that while God is love, love is not God. If you worship love and love becomes your God, it becomes your demon. CSL categorized love into four types such that we might, in some infinitely small measure, comprehend the parts of it better.

The first type of love CSL defines is storge, or affection, which you might think of as the humblest and most pervasive form of love, encompassing small things and large, and to qualify it as humble or small is not to diminish its beauty or significance. You might feel affection for anything from chocolate to your Siamese cat to your firstborn.

CSL begins his treatise with the two broader definitions of Gift-love and Need-love. The love/affection of a mother for a child is both Gift-love in that she is giving life, giving nourishment, giving safety; however, it is also Need-love in that she must give birth or die; breastfeed, or suffer; provide safety and life, or genetically perish.

The second type of love is philia, or friendship that arises from shared interests or a common view, causing two or more individuals to come together in such a way that they are no longer a part of the main. You can have an affection for chocolate, but it cannot be a friend. You may have a great deal of affection for your fourteen-year-old daughter or son, but they are not necessarily your friends and may never be. It may be easier to have an emotionally healthy friendship with Tinkerbell or Bruno than your progeny, but your affection for your progeny, if not a Gift-love, is at least a Need-love because, without them, your family line will be no more. This may sound trite or melodramatic now, but in the beginning, it meant the survival of the species.

The third type of love is eros, and now things become interesting because this includes that. CSL refers to that as Venus, the portion of eros that is the physical sexuality, as opposed to the other portion representing a deep emotional attachment and desire for the beloved. It is the latter portion that is specific to humanity in the sense of being made in his image. There is certainly Venus in a pride of lions, several times a day, I understand, but there is not the capacity for that other, more sublime part. Only man can appreciate it on the elevated plane it deserves. Only man can reason on it, draw inferences from it, paint pictures on cave walls of it, and carve representations thereof from blocks of stone. The lion does not do that.

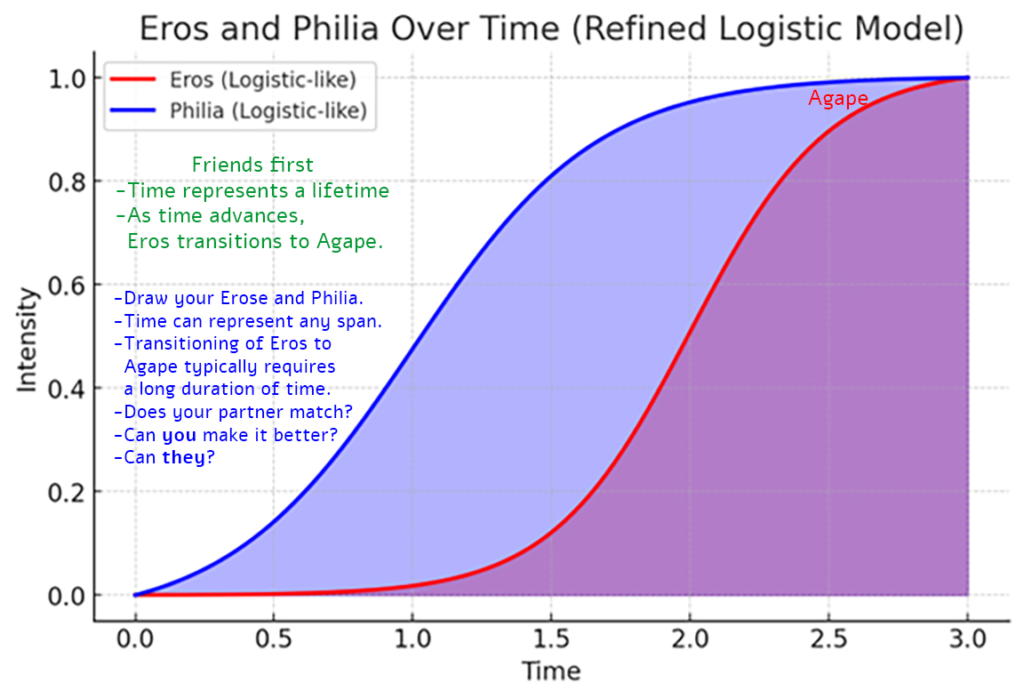

Eros is primarily a Need-love, especially in the beginning. It may progress to an elevated, more angelic phase of Gift-love, or it may not, which is not a bad thing as there is always philia, which is typically a strong accompaniment to eros and a necessary adjunct in a long-term, loving relationship. It is the relationship between these two loves that commands my attention for the purpose of mathematical application.

CSL describes eros as two lovers facing one another and philia as two lovers facing forward toward a shared purpose. While eros is typically between two, friendship is commonly not. There is no specific limit on the number of friends, and having more than one offers safety, a safety that is particularly evident when one member of a group of three or more is lost. With a denominator of 2, the loss of one is severe, whereas with a denominator of 3 or more, the loss of one is shared and less severe.

The final and perhaps highest love is agape, or charity. It is purely Gift-love, a self-sacrificing love. The supreme illustration is Christ dying on the cross, or to humanize it further, St. Theresa working in the slums of Calcutta. There are small acts and large, with the only limit being your devotion, conviction, faith, resolve, or capacity to give anything in any measure. It is perhaps not the most common love in most people’s lives most of the time, but its potential is always there.

There. Now that’s out of the way, I can discuss what I really wanted, namely love not between lions, but between any two creatures made in his image, which is to say—us. Between any two people in love, at least one of the four types of love—storge, philia, eros, or agape—must exist, or it cannot be love, by definition. Most likely, the love between two is not one type of love in isolation; rather, it is an amalgam of two or three or even four with varying fractions over time, not that that is terribly important other than too much of one or too little of another, or a gross asymmetry of the portions between the two lovers might manifest destructively.

Consider two complete strangers in Daytona Beach on a Spring Break vacation. Their eyes meet from other sides of a volleyball court on a beach. One espies the softness of a barely covered unbound breast through the haze of a webbed black net, while the other appreciates the broadness of shoulders above a narrow washboard-like waist. The emotion is perfectly symmetrical. Eros spikes. There is no storge, much less philia, for the simple reason that one does not know the other. There is no agape. It is all need; burning, obsessive, unrelenting, painful, wanting desire, a fire reaching to heaven that can only be wholly extinguished under the firehose of Venus. Oftentimes, on spring break, I suspect it is extinguished; however, I further suspect that the respective proportions of eros are rarely so perfect, so evenly matched. Most of the time, I imagine, it is decidedly a one-way passion in which the one consumed by eros is not extinguished, and if so, it is at the cost of the other doing so out of a warped act of charity in a Venusian act of mercy towards the other.

Regardless as to whether eros is mostly one-way or experienced in more equitable portions, one thing is certain: It is a mathematical impossibility that it would ever be perfectly, evenly matched. One will always experience it more than the other, but that’s not the important part. The important part is whether or not the other types of love, of any duration, come of it. If not, it is the equivalent of a one-night stand. All eros and not much else. It is brief, hot, passionate, or not. It could be a disappointment and potentially destructive because one always needs/wants more than the other. There is too much room for jealousy, anger, spiritual or emotional harm, or even hate in the cavernous space left by the absence of philia, charity, and affection.

Consider two people who meet for the first time on either side of a twelve-inch reflector scope at midnight to view the rings of Saturn on a moonless night during a meeting of the local astronomy club. It’s dark out but for the ambient glow of a weak red light. They don’t see each other, but they talk. One discovers that the other writes poetry and recites a favorite line, “The stars are not wanted now; put out every one, Pack up the moon and dismantle the sun.” And the other replies, “Pour away the ocean and sweep up the wood; For nothing now can ever come to any good.” At that precise moment, at the completion of WH Auden’s Funeral Blues, they become friends, joined by a mutual philia.

They talk through the night, and at dawn’s first light, they see each other for the first time. Eros spikes, or maybe not. Maybe one is twenty and the other sixty. Maybe one is comely and the other homely. If that is the case, perhaps eros sleeps undisturbed, but what if? What if there is any reasonable approximation in age and mutual attraction? Perhaps eros awakes. Perhaps eros spikes. Perhaps they rip off their clothes and fall, wanton, gasping, breathless to the ground, and become one flesh, but probably not, because they are not lions. More likely, they will exercise reason, restraint, and delay of gratification if there is to be any Venusian gratification at all. Two months pass. They discover one cannot live without the other. They become the closest of friends, the most passionate of lovers. There is nothing one would not do for the other. They get married. Each is entirely within the other. Everything is perfect.

If you haven’t already surmised, the above considerations between two people approximate the extremes, the flattest and most attenuated beginning and end of love’s bell curve. One could begin at one extreme and still end up at the other. Love takes effort, as all good things do. There is much pain and suffering between here and there, and ultimately, there is always the ultimate loss, as beautifully expressed in another of CSL’s works, A Grief Observed, which I read immediately after The Four Loves.

When one says, “It was love at first sight,” what do you think that is? It has to be eros because you are at time zero. There was no time for philia or affection, much less charity. If both are so afflicted, then you have the beginning of perfection, but it never remains so because, well. Life. One will not feel eros to the same extent as the other, perhaps not at all, perhaps the thought doesn’t occur to them for whatever reason—maybe an age discrepancy that, at 16, seems more significant than at 35; maybe a marriage stands in the way. But that doesn’t matter. What matters is, at the minimum, there must be storge, affection, and whether philia will develop. If it does, anything is possible.

It may be days. It may be weeks or years later before eros is disturbed between two connected by friendship. It might happen so gradually that you are surprised one morning by the appearance of an aching need that wants extinguishing that wasn’t there the night before. Or it may happen abruptly at a wedding celebration when a bridesmaid dances with her groomsman, or on a chilly night under a full moon when two share a trembling, tremulous New Year’s Eve kiss and Eros awakens. Then it begins.

0 Comments