SJ Melarvie

I hope all the good stuff isn’t already written.

ABOUT SONG OF SONGS

THE SONG OF SONGS is a dual POV, 99k-word manuscript of book club fiction with mystery and thriller elements. It’s not a road trip story. It’s two road trip stories when two boys embark on a 4000-mile quest for love and adventure, then have to repeat the trip 40 years later to fix a problem from the first, and everything else they spent a lifetime breaking. The underlying theme of enduring friendship would appeal to readers of Tomorrow, Tomorrow, and Tomorrow by Gabriella Zevin, especially children of the 80s, and bad Catholics.

At 60, widowed and broken, Johnny answers the phone the day before he decides to end it all. It’s his estranged best friend, Dave, divorced, and living off his father’s inheritance. He asks Johnny to repeat the their trip to Tijuana they took when they were 17, because Johnny has to help him with something. Johnny agrees because he owes Dave for saving his life after a bad acid trip in a state park overlooking the Pacific, besides the fact that he was about a minute from his final solution. It was a sign.

But now, they’re almost old men, nostalgic for simpler times, and must deal with all their adult problems. Dave plans to use his father’s clandestine adult western, which he knows Johnny read as an adolescent, to reconnect by spending a few days at the dude ranch that served as the setting for The Virgin Temptress. Although they rediscover their love lost, it is not enough to heal Johnny’s brokenness. That requires the intervention of a Tijuana sex worker who became a saint, and is the mother of Carmelita, who is the origin of Dave’s problem from the first trip.

1: 2022: Black Holes (exerpt)

I opened my eyes on the first day, not sure where I was or how I got there, which happened to be stretched out diagonally on our bed, my head on her side, arms outstretched like I’d been crucified; then I remembered the pills my internist friend gave me. “Just a few to get you through the next few nights, Johnny,” he had said. The fan blades turned slowly above me. I wasn’t even sure how to turn it on. It’s something she always did, a remote control I remembered, a white one, with white buttons. I had to pee. That’s all I remember from the first day, peeing. Peeing and answering the phone on my back, watching the fan blades turn, the soft metronomic tsk, tsk, tsk, a mental pacifier for adults, thinking that she had turned them on, and I would never turn them off, thinking of her, thinking of what was, of how she looked at me in our last minutes, of what she said, of what I said.

I had fallen into a deep, black hole and was looking up at a small circle of light in which all I could see were fan blades, turning, then I realized I was the hole. Hannah was gone. She had been my event horizon, her touch, her look, her voice, her soul, and she had sucked me in happy, joyous, young, and now I had been spit out on the other side, wretched, joyless, old, and into an alien universe in which I didn’t belong.

The second day, I climbed on the Trek 5500 I had impulsively bought on a summer day when we stopped at the bike shop in Fish Creek. “It looks good on you, Honey,” she says, and I smile back and plunk down the four thousand or whatever dollars it costs because it was the same model Lance Armstrong had won the Tour de France with. Tearing down Monument Bluff Road at over 40 miles an hour, the air screaming through my hair because I left my helmet at home, almost weightless, I blinked away sweat, or tears?—I couldn’t tell—I realized that if I pedaled hard enough, fast enough, long enough, I stopped thinking. All I needed was water. I didn’t even pee much. As the sun began to set, I turned back for home. I don’t know what time it was when I collapsed in bed. Above me, the fan blades she had turned on turned.

The third day, I was tired, so I sat at my desk, my safe space, windows to the front and sides, surrounded by the lake, like I was standing on the bow of a ship, the Titanic, maybe. The floor-to-ceiling drapes she had made from a sepia-toned linen with pale ships of billowing sails and whaling boats filled with men were open, the water blue and calm as far as the eye could see. She had found the fabric one day at Hobby Lobby. “You like this?” she asks. “It will go with Sergio’s mask.” I say that I love it, that it reminds me of Moby Dick. “You’ll have to hang a wrap-around curtain rod,” she threatens. “Happily,” I say back, petting the roll of fabric.

I swiveled to my right, where I knew the boxed set of Marcel Proust’s In Search of Lost Time was. She had given it to me the Christmas of 2001. I remembered the year because it was after 9-11. I pulled Volume I from the box, Swann’s Way. I started to read. Then I had to pee. That’s all I did the third day. I peed. And I read. And music.

I turned it on. Not that I didn’t every day before, but it now seemed more significant because I couldn’t stand the sound of silence. So, that third day, when I sat at my desk for the first time since she…and started to read, I stopped, because of the silence. I pulled out my phone, opened Spotify and tapped my Favorites of All Time playlist. It would last over 12 hours and contained every song I had ever liked at some point in my life. I selected the source Basement, where the multi-zone amp connected to Alexa lives. And the music played, until I couldn’t read anymore. Then I took my black hole to bed and watched the fan blades turn, made ghostly in the moonlight through the window, like maybe I wasn’t real anymore. “Tsk…tsk…tsk,” they said.

The fourth day, I paced myself. I rode, then I read at my desk by the light of the Hula-girl lamp with the muted sepia shade we had found on the Big Island. “This will go with your drapes,” she says. “I love it,” I say back, tickling pale gold tassels on the bottom of the shade with my finger.

And the music played. Eventually, I couldn’t keep my eyes open. I tried picturing Odette de Crecy, Charles Swann’s obsession, but she looked strangely like Raquel Welch. Then the fan blades turned, talking to me, but now there were two counts instead of one. I tried forming the first palatal consonant with my tongue, maybe like a soft ‘G.’ “Juh, jee, j…” I said, but then everything went away.

Of course, there was always a way out. It was the first thing I thought of, but that was a sin. A bike accident would not be a sin, but that hadn’t happened yet, although there was always hope. But I had a sure thing, even on the third day, sitting at my desk, reading, listening to music, my legs all the way under, it was there, its cool metallic edge off the top of my right knee.

I had won it accidentally in a raffle. I really wanted the shotgun because I thought I’d take up skeet shooting, but that was the next basket over. “What are you afraid of?” she says as I’m screwing a magnet to the underside of the Roosevelt desk we’d found at an antique store. I know she’s laughing at me, even if I can’t hear it as I lie under the desk in my favorite T-shirt, the one with a mug of Guinness and the caption Hello Darkness, my old friend. I drive home the final screw with a final sweaty grunt, complementing myself over the foresight to have measured the thickness of wood between the bottom of the desktop and its leather surface. “I’ll know it when I see it. Besides, it seemed like a sign.” I say, choosing not to share my fantasy of some dirtbag with a gun barging upstairs while I’m in my office when she’s around the corner in the bonus room working on the quilt she calls her Theory of Everything. “Say ‘Hello’ to my ‘lil friend, Dirtbag,” I say cooly, and not all that surprised. I see the answer in his eyes before he can actually pull the trigger, and make a booming window, trimmed out in red, where his heart used to be. Hannah rushes into my arms. “Thank God, you bought that gun, Johnny,” she says. Then I hear her voice for real. “What?” I say, and she says to just be careful. I lift the .45 Kimber 1911 with a laser sight built into the handle. I wonder if the magnet is strong enough. The gun leaps from my hand with an ominous, muted clunk. It is.

The fifth day was the funeral, closed casket so no one could see the angular gauntness of her face that was still oh so beautiful. After everyone had left, saying how they’d keep in touch but knowing they wouldn’t, I climbed on my bike. I knew the drill.

The sixth day, everything stopped. I deleted the shitty novel I had been working on the past three years from my hard drive. I officially stopped working, resigning from the medical staff because after 30 years of being a surgeon, no kids, and a rich mother, I didn’t have to. The only thing that didn’t stop was me thinking of her, so I climbed on my bike. I read Swann’s Way. The music played. The fan blades turned. But now I knew what they were saying. “Judas. Judas. Judas,” they were saying. And I peed in between all of that. Would there be life after Marcel? I had no idea, but I promised myself I would wait until then, riding without a helmet, hoping to avoid the sin I would commit if there was.

Twenty-one days, 1000 miles, three masses, two confessions with Fr. Ryan, and 2000 and some pages later, I lifted my head from the last volume, Finding Time Again. The lake, more gray than blue, displayed evidence of wind in white caps and lines of frothy white rollers crashing into the bluff below. A large storm cloud, halfway to the horizon, dropped a curtain of rain that looked like a wide, harmless, dirty-white tornado behind which there was a soft yellow-orange light, almost glowing. I didn’t know if it was morning or evening. It should have been beautiful. I recognized that at least, but it wasn’t. Nothing had changed. Marcel? God? Neither had been enough to make a difference.

I looked at the Venetian mask centered above the sliding doors. We had found it in a mask shop off the Rialto Bridge 25-years earlier. When I pointed at it, Sergio, the mask maker, said, “I call it The Three Faces of Man.” He became famous. It’s probably worth 40 large by now. Joy. Anger. Despair. Three faces in a common head, left to right, gilded in gold with black in the folds, in the eyes, the middle mouth opened in a black silent scream. I know which one I am. I looked down at my book. Marcel’s visiting Gilberte, now Mme de Saint-Loup, in Tansonville, by Cobray, but the words are blurry, then drops are falling.

Crying? I’m crying? I didn’t understand because that only happened on the bike, and I didn’t feel sad. It’s like I was already dead. So what if I stopped? What difference would it make? Nothing really matters—whispers Freddy from across the universe, and through the speakers, One Tin Soldier starts playing—“Listen children, to a story”— The Kimber presses insistently into my knee. Its darkness calls. “I’m here,” it says. “Pick me,” it says.

You Fuckin’ Loser I say to myself.

And just like that, I know. I knew my story was done. God? Yeah…Right. Fuck it. He’ll do the right thing, on the outside chance He’s even there.

No need for the laser sight. Hello darkness, my old friend. I almost chuckled, my heart pounding away, everything looking overly bright, me all sweaty and breathing like there wasn’t enough air in the room.

But then…

2: 1981: Summer's End (exerpt)

I pulled into Dave’s driveway Saturday afternoon, next to the candy apple red Nova Super Sport from his uncle’s lot he had been saving up for. It made my small block Challenger with the dent and scratched blue paint look pretty tame. His parents were waiting for us on lawn chairs in the front yard, drinking beer and eating Russian peanuts. Dave had called them collect from South Dakota when we stopped for a burger, so they knew when we’d get there.

Dave’s dad said they had a surprise for him, but it still blew Dave away. He was all over it, touchin’ it, strokin’ it, opening the doors, sitting in it, caressing the stick shift like it was his dick and shit, so I did most of the talking.

“Welcome back, Johnny,” Mr. Armstrong said. He spit out some shells, “Good to see you made it in one piece.”

“No problemas,” I said, but then remembered our most recent. “Except for some overheating in Death Valley.”

“What’d you do?”

“Turned on the heater.”

“Yeah?”

“Read it in a magazine. Worked like a charm.” I didn’t say anything about driving off the road.

Mr. Armstrong was checking out my Challenger. “What’s with the dent and scratch?” he said, pointing at the paw print in my fender.

“Uhh…that was a bear encounter in Yellowstone.”

Mr. Armstrong raised his eyebrows, and when he started to open his mouth, I cut him off real quick, “I’ll let Dave fill you in on that.” Luckily, Mrs. Armstrong was noticing her gift.

“What’s tha—”

“That’s for you, Mom,” Dave said, somehow translocating from the front seat of his Nova back to the passenger side of my car. I hadn’t even seen him move. He pulled out a four-foot-high ceramic vase painted in the bright colors of Tijuana. I remembered when he haggled for it on Revolución, right after scoring on a Linda Ronstadt black velvet painting. “Why in the fuck did you have to buy such a big fuckin’ vase?” I had asked, “It’ll take up the whole seat.” “It’s for my mom,” was all he said, like it was answer enough. And it was. I could see that now in the way his mother smiled, in the way they hugged. Made me feel like a creep for giving him such a hard time over it.

“Well, I’d better get going,” I said. I knew my mom and dad were anxious to see me. I’d just have to go see them separately.

Dave came over and leaned against the Challenger next to me. “Well, Johnny. We did it. We made it to land’s end.”

“And back,” I said, without further elaboration of all the seed we had spilled or how many times we had cheated death.

“Turns out we never needed the big tent.”

“Next time,” I said.

He looked at me. I looked at him. There really were no words because we could read each other’s minds. “Okay then. I’ll pick you up tomorrow in my big block.”

“Great. I’ll drive my little block home now.”

“See you in about…” Dave said, looking pointedly at his Timex, “Twenty-two hours?” We both laughed, his parents in the background, Mr. Armstrong’s arm around his wife. It was like they weren’t even there, just Dave and Johnny, best friends forever.

Dave picked me up in his big block, all red and gorgeous, rumble-rumbling in the driveway like it was about ready to rocket into the sky trailing a plume of smoke. Who cared if it only got eight miles to the gallon?

“Hey, Johnny. Guess everyone’s going to the falls this afternoon ‘cause it’s so fuckin’ hot. Hop in, pardner.” He smiled, his teeth looking especially white against his summer’s end tan.

I already had my cutoffs on, so I was good to go. I hadn’t known where we were going to meet up, but the falls sounded damn good. It was only a little further downstream from where Savannah had revealed herself before our trip. I was happy to pass that hallowed ground again, thinking maybe I should have taken a plaster cast of her footprints in the mud the last time we were there. “Give me a sec. I’ll grab a towel, and I gotta get a twenty for Gary. I still owe him from before our trip.”

The waterfall was small, only a few feet high, the river little more than a creek, so you could walk into flowing water no more than four feet deep, then dunk under the falls and come up behind it. I don’t even think anyone ever drowned there. Then you could stand still, behind the falls, all wet and shiny and covered in mist, and breathe in the moist, earth-wormy scent of it while marveling at the thundering feel of water cascading down in front, only inches away. It looked like a sheet of liquid glass, a moving, churning mass of translucent whites and at least 40 shades of green that was too thick to see through but thin enough to let in the light. It felt like you were behind a living, breathing, magical lens of all the green in the world.

In that narrow space behind the falls, I felt like a fish underwater, breathing through gills I didn’t have, like I’d just stuck my head out of the primordial soup, all alone on a virgin planet. I liked sticking my hand out to feel the hardness of the water against my skin. It hurt so good, and standing there, waist-deep in the whirlpool of frothy roiling water filling my clothes with its fecund air, was like being impregnated by life itself. I loved it.

When we got there, I was saddened to see Savannah wearing cut-offs and a white T-shirt instead of her leopard suit. I was further saddened to see Duane by the beer cooler, but I didn’t know if he had come with her or if they were even going out still. It was hard for me to focus on anything else but Savannah, but I tried so as I wouldn’t look like a total perv. It was easier when she jumped into the river with some friends; that way, I could just look in the general direction.

Gary was tossing around a football with a couple of other guys, and that looked like fun, so Dave and I jumped in. Gary threw a spiral, and Dave laid out for it, parallel to the water. He missed, but still looked cool. It must’ve been 100 degrees and humid, so most of us were in the water by now.

Without my glasses, I couldn’t see shit, and just as likely to catch the ball with my face as with my hands, so I took a deep breath and went down under. That’s at least one thing I was better at than anyone else. I could hold my breath for almost forever. I swam towards the falls. I could tell I was close because of the current and bubbles. About a minute later, I reached out my hand for the wall and grabbed someone’s upper thigh. I let go, embarrassed, and emerged from the primordial soup, right next to Savannah.

She smiled, her T-shirt clinging to her like it wasn’t even there. All I could see was her and her cold nipples sticking out. I forgot I had to breathe, until I did. I gasped, feeling more desire than I’d ever felt before, even in Tijuana, and it was like old times. I throbbed down under. You’d think I’d have known what to do because I’d already done it. I would just wrap her in my big, strong arms and crush her to my broad chest and bury my tongue, gently, softly, sweetly, into her mouth on the other side of those perfect lips. But I didn’t. I froze.

I looked stupid, standing there, staring fixedly at her nipples, at her face, her eyes, her mouth, the whole completeness of her, like maybe I thought I was clairvoyant and transmitting my love to her through my eyes alone. It just looked like I was looking at her nipples. She giggled. I looked into her eyes more specifically. They were the same color as the water cascading past, like there was a little waterfall inside her. I couldn’t speak. Her beauty overwhelmed me. I was a coward. I tasted her name slowly, “Sa-van-nah,” each syllable rolling around my mouth, taking shape in celebration of her sensuality.

Her lips strained against laughter, trying to come out. She couldn’t do it. I couldn’t stand it. I dove back under the water so she wouldn’t see my tears, the sound of her laughter a torture as I swam with the current against the muddy bottom, bumping into branches, boulders, and other legs until I came up, sucking for air, far, far out of sight.

It was after that afternoon that Dave and Savannah started going together. I never asked if he met her under the waterfall or what. I didn’t want to know. I only wondered what she’d have done if I had done what I wanted to do, if it could have been me.

Why Melarvie.com?

Although I’ve been writing all my life, I have read far, far more than I have ever written. I have won a few writing contests and have had a short story published (below); however, I remain a better reader than a writer, if only for the relative time expended; nonetheless, I have finished my first novel. With this site, I wish to increase my online presence beyond that of just a surgeon and also to blog about what I’ve read and other interests. Thank you for your interest.

This draft cover was generated by ChatGPT.

Jorge Luis Borges' Aleph

“Under the step, toward the right, I saw a small iridescent sphere of almost unbearable brightness. At first I thought it was spinning; then I realized that the movement was an illusion produced by the dizzying spectacles inside it. The Aleph was probably two or three centimeters in diameter, but universal space was contained inside it, with no diminution in size…saw the Aleph from everywhere at once, saw the earth in the Aleph, and the Aleph once more in the earth and the earth in the Aleph, saw my face and my viscera, saw your face, and I felt dizzy, and I wept, because my eyes had seen that secret, hypothetical object whose name has been usurped by men but which no man has ever truly looked upon: the inconceivable universe.

I had a sense of infinite veneration, infinite pity.”

From Collected Fictions, translated by Andrew Hurley.

Shaun J Melarvie

Author

My Story

I’ve wanted to be a writer for as long as I’ve been a reader, although in college, after failing to produce an income writing after my first creative writing class with Robert King at the then Bismarck Junior College, I pragmatically enrolled in a pre-med curriculum. After the second semester, my first B, and hours spent in labs mixing this with that, I cried uncle and switched my major to English Literature. Two years later, my GPA was back above 3.8. I had won a prize for a short story but was not yet on the doorstep to fame, and I, again, pragmatically, switched back to pre-med. I discovered that my grades were directly proportionate to my time studying, and, in five years, I graduated Summa Cum Laude from the University of ND and, four years after that, from the School of Medicine.

I am now almost old, mostly done with medicine, and finally doing what I’ve wanted to do all along, at least more than I had done previously. My first novel is called The Song of Songs. I hope that someday, you will be able to read it.

Please visit below for non-fiction medical writing, if interested in weight loss, or to read one of my short stories, respectively.

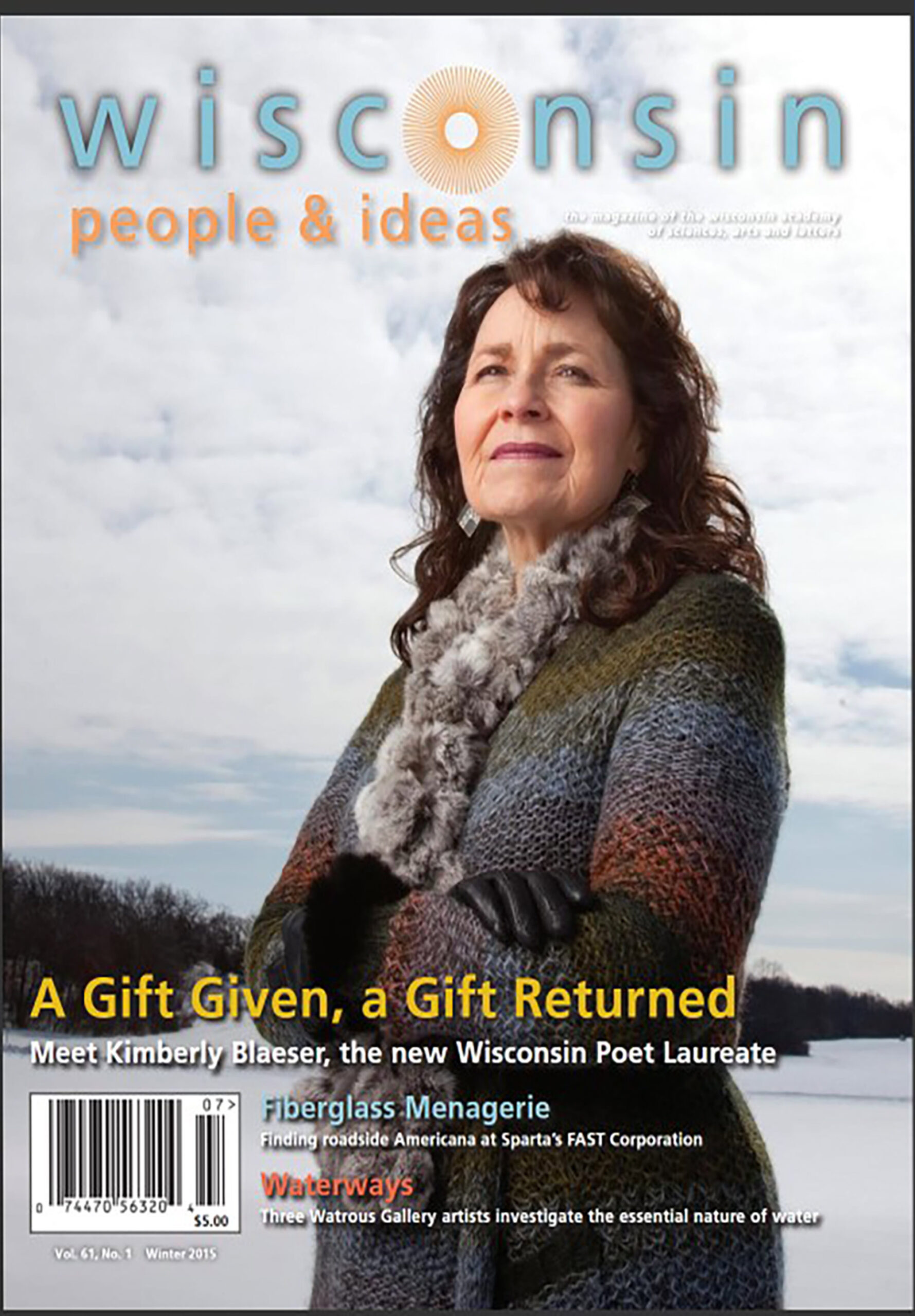

The Dying Man

I’ve almost died more than most people, the first time in 1963 at age two when my father struck me four times forcefully while holding me upside down, straddling his arm to dislodge the clump of Pablum obstructing my airway. I’m not positive he was up to date on the Basic Life Support relative to choking, which was invented in the early 60’s. I don’t remember that, but I remember the depressed skull fraction and loss of a goodly portion of my right temporal lobe at age four, the pit of vipers in Belize at 16, falling asleep at the wheel at 23, the pericardial effusion at 38, going over the bridge headfirst at 46, breaking C-1, C-2, C-6 bodysurfing at 63; but, it was the curious events of 2018 that made me think more specifically of death because I had the time to do so as I was dying more slowly, or so I thought. I started an anonymous blog, TheDyingMan.com, because I had to do something, but it was too personal to share because it seemed too self-indulgent at the time; however, time has passed, mother is gone, it was not that long ago I lay dying on a beach with a broken neck, and one of the posts was the source of inspiration for Angelsong, which took 1st as a creative non-fiction entry in the 2023 Hal Prize, plus, I need to prove I can write reasonably well, even if having a fondness for the overuse of overly long sentences. That’s why God invented editors. The site is a time capsule, which will last as long as I do. I stopped posting on it, so it is already dead, which has a certain symmetry that appeals to me.